One of the best pieces of advice I've seen

Mar 21, 2020 01:59:17 #

whitnebrat

Loc: In the wilds of Oregon

Washington Post

By

Kim Bellware

March 20, 2020 at 5:42 p.m. PDT

As daily life undergoes rapid changes in response to the c****av***s outbreak and the death and infection total climb, a Chicago epidemiologist is drawing praise for her comments at a Friday news conference that outlined with clarity and urgency how seemingly small sacrifices today will prevent deaths of loved ones and strangers next week.

Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at University of Chicago Medicine, took the lectern after Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D), who on Friday afternoon announced that the state would undergo a shelter-in-place order for 2½ weeks starting Saturday evening.

“The healthy and optimistic among us will doom the vulnerable,” Landon said. She acknowledged that restrictions like a shelter-in-place may end up feeling “extreme” and “anticlimactic” — and that’s the point.

“It’s really hard to feel like you’re saving the world when you’re watching Netflix from your couch. But if we do this right, nothing happens,” Landon said. “A successful shelter-in-place means you’re going to feel like it was all for nothing, and you’d be right: Because nothing means that nothing happened to your family. And that’s what we’re going for here.”

Landon’s comments were less than 10 minutes of the nearly hour-long news conference, but they quickly made an impression on listeners and drew praise for their clarity and sense of empowerment while still conveying the urgency of the moment.

The positive reactions to Landon’s remarks were already making their way to her phone when she spoke to The Washington Post a short time after. Landon described herself as naturally optimistic, the kind of person who wants to see the bright side of things, but said that the United States is in a critical moment where people need to understand the seriousness of the crisis and how their seemingly small actions can affect it.

“In all honesty, if we say, ’This is like the flu, we’ll be all right,' that attitude is going to harm other people,” Landon told The Post. “And it’s really hard to wrap your head around that, especially in American culture: We’re individualistic and we pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and find a way to make it through. And that’s not going to work right now.”

Valerie Gunn, a marketing professional in Chicago, said Landon struck a chord.

“She was very human, and I thought she did a good job of sounding the alarm without making me feel like I need to go buy everything in the grocery store,” Gunn told The Post by phone Friday. “If you listen to not one other speech about this, this is the one I would listen to. It was concise and absorbable.”

Gunn said Landon’s remarks provided a useful road map for helping people understand the outcomes health officials are hoping for, and helped retool her perspective so that she won’t feel frustrated if the drastic measures, as Landon said, feel like they were “all for nothing.”

For Michael Patrick Thornton, an actor and theater creative director in Chicago, Landon’s comments provided the information and professionalism he’s found lacking in the federal government’s remarks, including those of President Trump.

Thornton told The Post he listened to Landon’s comments and heard “a very clear story about shared responsibility in a time of p******c.”

“People are trying to wrap their minds about what fighting this even feels like, and she did a masterful job in managing expectations,” Thornton said.

In Illinois, there are at least 585 confirmed cases of c****-** and four deaths. Yet Landon said she recognizes (and has seen) that many people still doubt that skipping book club or soccer practice can make a difference in the v***s’s spread; she understands that the sentiment might be felt especially strongly in Illinois’ more-rural communities that have yet to confirm a case of infection.

“The other communities are the ones who will benefit the most from doing a shelter-in-place now,” Landon said. “That’s why statewide shelter-in-place orders are the most effective.”

The cases coming into hospitals now are patients who were infected a week ago, and if communities wait until the hospitals are full to start their self-isolation, she said, "next week’s patients won’t have anywhere to go.”

By

Kim Bellware

March 20, 2020 at 5:42 p.m. PDT

As daily life undergoes rapid changes in response to the c****av***s outbreak and the death and infection total climb, a Chicago epidemiologist is drawing praise for her comments at a Friday news conference that outlined with clarity and urgency how seemingly small sacrifices today will prevent deaths of loved ones and strangers next week.

Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at University of Chicago Medicine, took the lectern after Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D), who on Friday afternoon announced that the state would undergo a shelter-in-place order for 2½ weeks starting Saturday evening.

“The healthy and optimistic among us will doom the vulnerable,” Landon said. She acknowledged that restrictions like a shelter-in-place may end up feeling “extreme” and “anticlimactic” — and that’s the point.

“It’s really hard to feel like you’re saving the world when you’re watching Netflix from your couch. But if we do this right, nothing happens,” Landon said. “A successful shelter-in-place means you’re going to feel like it was all for nothing, and you’d be right: Because nothing means that nothing happened to your family. And that’s what we’re going for here.”

Landon’s comments were less than 10 minutes of the nearly hour-long news conference, but they quickly made an impression on listeners and drew praise for their clarity and sense of empowerment while still conveying the urgency of the moment.

The positive reactions to Landon’s remarks were already making their way to her phone when she spoke to The Washington Post a short time after. Landon described herself as naturally optimistic, the kind of person who wants to see the bright side of things, but said that the United States is in a critical moment where people need to understand the seriousness of the crisis and how their seemingly small actions can affect it.

“In all honesty, if we say, ’This is like the flu, we’ll be all right,' that attitude is going to harm other people,” Landon told The Post. “And it’s really hard to wrap your head around that, especially in American culture: We’re individualistic and we pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and find a way to make it through. And that’s not going to work right now.”

Valerie Gunn, a marketing professional in Chicago, said Landon struck a chord.

“She was very human, and I thought she did a good job of sounding the alarm without making me feel like I need to go buy everything in the grocery store,” Gunn told The Post by phone Friday. “If you listen to not one other speech about this, this is the one I would listen to. It was concise and absorbable.”

Gunn said Landon’s remarks provided a useful road map for helping people understand the outcomes health officials are hoping for, and helped retool her perspective so that she won’t feel frustrated if the drastic measures, as Landon said, feel like they were “all for nothing.”

For Michael Patrick Thornton, an actor and theater creative director in Chicago, Landon’s comments provided the information and professionalism he’s found lacking in the federal government’s remarks, including those of President Trump.

Thornton told The Post he listened to Landon’s comments and heard “a very clear story about shared responsibility in a time of p******c.”

“People are trying to wrap their minds about what fighting this even feels like, and she did a masterful job in managing expectations,” Thornton said.

In Illinois, there are at least 585 confirmed cases of c****-** and four deaths. Yet Landon said she recognizes (and has seen) that many people still doubt that skipping book club or soccer practice can make a difference in the v***s’s spread; she understands that the sentiment might be felt especially strongly in Illinois’ more-rural communities that have yet to confirm a case of infection.

“The other communities are the ones who will benefit the most from doing a shelter-in-place now,” Landon said. “That’s why statewide shelter-in-place orders are the most effective.”

The cases coming into hospitals now are patients who were infected a week ago, and if communities wait until the hospitals are full to start their self-isolation, she said, "next week’s patients won’t have anywhere to go.”

Mar 21, 2020 02:04:10 #

whitnebrat wrote:

Washington Post br By br Kim Bellware br March 2... (show quote)

Good article... Good advice...

I'm almost finished my second month of "shelter in place"...

Mar 21, 2020 02:17:41 #

whitnebrat wrote:

Now, let's see how a professional epidemiologist who isn't a political hack in Chicago analyzes this v***s thing.Washington Post br By br Kim Bellware br March 2... (show quote)

A fiasco in the making? As the c****av***s p******c takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data

by Dr. John P. A. Ioannidis.

The current c****av***s disease, C****-**, has been called a once-in-a-century p******c. But it may also be a once-in-a-century evidence fiasco.

At a time when everyone needs better information, from disease modelers and governments to people quarantined or just social distancing, we lack reliable evidence on how many people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who continue to become infected. Better information is needed to guide decisions and actions of monumental significance and to monitor their impact.

Draconian countermeasures have been adopted in many countries. If the p******c dissipates — either on its own or because of these measures — short-term extreme social distancing and lockdowns may be bearable. How long, though, should measures like these be continued if the p******c churns across the globe unabated? How can policymakers tell if they are doing more good than harm?

V*****es or affordable treatments take many months (or even years) to develop and test properly. Given such timelines, the consequences of long-term lockdowns are entirely unknown.

The data collected so far on how many people are infected and how the epidemic is evolving are utterly unreliable. Given the limited testing to date, some deaths and probably the vast majority of infections due to SARS-CoV-2 are being missed. We don’t know if we are failing to capture infections by a factor of three or 300. Three months after the outbreak emerged, most countries, including the U.S., lack the ability to test a large number of people and no countries have reliable data on the prevalence of the v***s in a representative random sample of the general population.

This evidence fiasco creates tremendous uncertainty about the risk of dying from C****-**. Reported case fatality rates, like the official 3.4% rate from the World Health Organization, cause horror — and are meaningless. Patients who have been tested for SARS-CoV-2 are disproportionately those with severe symptoms and bad outcomes. As most health systems have limited testing capacity, se******n bias may even worsen in the near future.

The one situation where an entire, closed population was tested was the Diamond Princess cruise ship and its quarantine passengers. The case fatality rate there was 1.0%, but this was a largely elderly population, in which the death rate from C****-** is much higher.

Projecting the Diamond Princess mortality rate onto the age structure of the U.S. population, the death rate among people infected with C****-** would be 0.125%. But since this estimate is based on extremely thin data — there were just seven deaths among the 700 infected passengers and crew — the real death rate could stretch from five times lower (0.025%) to five times higher (0.625%). It is also possible that some of the passengers who were infected might die later, and that tourists may have different frequencies of chronic diseases — a risk factor for worse outcomes with SARS-CoV-2 infection — than the general population. Adding these extra sources of uncertainty, reasonable estimates for the case fatality ratio in the general U.S. population vary from 0.05% to 1%.

That huge range markedly affects how severe the p******c is and what should be done. A population-wide case fatality rate of 0.05% is lower than seasonal influenza. If that is the true rate, locking down the world with potentially tremendous social and financial consequences may be totally irrational. It’s like an elephant being attacked by a house cat. Frustrated and trying to avoid the cat, the elephant accidentally jumps off a cliff and dies.

Could the C****-** case fatality rate be that low? No, some say, pointing to the high rate in elderly people. However, even some so-called mild or common-cold-type v***ses that have been known for decades can have case fatality rates as high as 8% when they infect elderly people in nursing homes. In fact, such “mild” c****av***ses infect tens of millions of people every year, and account for 3% to 11% of those hospitalized in the U.S. with lower respiratory infections each winter.

These “mild” c****av***ses may be implicated in several thousands of deaths every year worldwide, though the vast majority of them are not documented with precise testing. Instead, they are lost as noise among 60 million deaths from various causes every year.

Although successful surveillance systems have long existed for influenza, the disease is confirmed by a laboratory in a tiny minority of cases. In the U.S., for example, so far this season 1,073,976 specimens have been tested and 222,552 (20.7%) have tested positive for influenza. In the same period, the estimated number of influenza-like illnesses is between 36,000,000 and 51,000,000, with an estimated 22,000 to 55,000 flu deaths.

Note the uncertainty about influenza-like illness deaths: a 2.5-fold range, corresponding to tens of thousands of deaths. Every year, some of these deaths are due to influenza and some to other v***ses, like common-cold v***ses.

In an autopsy series that tested for respiratory v***ses in specimens from 57 elderly persons who died during the 2016 to 2017 influenza season, influenza v***ses were detected in 18% of the specimens, while any kind of respiratory v***s was found in 47%. In some people who die from v***l respiratory pathogens, more than one v***s is found upon autopsy and bacteria are often superimposed. A positive test for c****av***s does not mean necessarily that this v***s is always primarily responsible for a patient’s demise.

If we assume that case fatality rate among individuals infected by SARS-CoV-2 is 0.3% in the general population — a mid-range guess from my Diamond Princess analysis — and that 1% of the U.S. population gets infected (about 3.3 million people), this would t***slate to about 10,000 deaths. This sounds like a huge number, but it is buried within the noise of the estimate of deaths from “influenza-like illness.” If we had not known about a new v***s out there, and had not checked individuals with PCR tests, the number of total deaths due to “influenza-like illness” would not seem unusual this year. At most, we might have casually noted that flu this season seems to be a bit worse than average. The media coverage would have been less than for an NBA game between the two most indifferent teams.

Some worry that the 68 deaths from C****-** in the U.S. as of March 16 will increase exponentially to 680, 6,800, 68,000, 680,000 … along with similar catastrophic patterns around the globe. Is that a realistic scenario, or bad science fiction? How can we tell at what point such a curve might stop?

The most valuable piece of information for answering those questions would be to know the current prevalence of the infection in a random sample of a population and to repeat this exercise at regular time intervals to estimate the incidence of new infections. Sadly, that’s information we don’t have.

In the absence of data, prepare-for-the-worst reasoning leads to extreme measures of social distancing and lockdowns. Unfortunately, we do not know if these measures work. School closures, for example, may reduce t***smission rates. But they may also backfire if children socialize anyhow, if school closure leads children to spend more time with susceptible elderly family members, if children at home disrupt their parents ability to work, and more. School closures may also diminish the chances of developing herd immunity in an age group that is spared serious disease.

This has been the perspective behind the different stance of the United Kingdom keeping schools open, at least until as I write this. In the absence of data on the real course of the epidemic, we don’t know whether this perspective was brilliant or catastrophic.

Flattening the curve to avoid overwhelming the health system is conceptually sound — in theory. A visual that has become v***l in media and social media shows how flattening the curve reduces the volume of the epidemic that is above the threshold of what the health system can handle at any moment.

Yet if the health system does become overwhelmed, the majority of the extra deaths may not be due to c****av***s but to other common diseases and conditions such as heart attacks, strokes, trauma, bleeding, and the like that are not adequately treated. If the level of the epidemic does overwhelm the health system and extreme measures have only modest effectiveness, then flattening the curve may make things worse: Instead of being overwhelmed during a short, acute phase, the health system will remain overwhelmed for a more protracted period. That’s another reason we need data about the exact level of the epidemic activity.

One of the bottom lines is that we don’t know how long social distancing measures and lockdowns can be maintained without major consequences to the economy, society, and mental health. Unpredictable evolutions may ensue, including financial crisis, unrest, civil strife, war, and a meltdown of the social fabric. At a minimum, we need unbiased prevalence and incidence data for the evolving infectious load to guide decision-making.

In the most pessimistic scenario, which I do not espouse, if the new c****av***s infects 60% of the global population and 1% of the infected people die, that will t***slate into more than 40 million deaths globally, matching the 1918 influenza p******c.

The vast majority of this hecatomb would be people with limited life expectancies. That’s in contrast to 1918, when many young people died.

One can only hope that, much like in 1918, life will continue. Conversely, with lockdowns of months, if not years, life largely stops, short-term and long-term consequences are entirely unknown, and billions, not just millions, of lives may be eventually at stake.

If we decide to jump off the cliff, we need some data to inform us about the rationale of such an action and the chances of landing somewhere safe.

John P.A. Ioannidis is professor of medicine, of epidemiology and population health, of biomedical data science, and of statistics at Stanford University and co-director of Stanford’s Meta-Research Innovation Center.

Mar 21, 2020 04:23:43 #

Blade_Runner wrote:

Now, let's see how a professional epidemiologist w... (show quote)

So why is Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Chicago Medicine, a hack and John P.A. Ioannidis a professor of medicine, of epidemiology and population health, of biomedical data science, and of statistics at Stanford University isn't a hack of equal proportions?

Blade, you are working under the assumption that if you agree with what you hear from someone then what you hear is true. That's because you think you know the t***h when you hear it even though your entire world is modeled out of logical fallacies and you surround yourself with people who tell you only what you want to hear. I don't know who is right Blade but with something as potentially dangerous as C****-**, I don't think it is something that we should fart around with. We haven't' dealt with C****-** so we can't treat it as if it is a cold or the flu.

That's the problem with your logic Blade, though one area I would agree with your Doctor is that there isn't enough data which is why we should be testing, testing, testing until we have some quantifiable results. Your president said that we only need to be testing if we show symptoms. Is he correct?

Mar 21, 2020 05:46:20 #

PeterS wrote:

So why is Emily Landon, the chief infectious disea... (show quote)

I heard a Dr. say they've had great results with chloroquine and by the 6th day, they're feeling very well.

Mar 21, 2020 06:38:13 #

PeterS wrote:

So why is Emily Landon, the chief infectious disea... (show quote)

====================

We are trying to analyze the best approach or best decision to take at the moment. C****av***s is first to happen we’ve never expected. We are caught unprepared.

Dr. John P. A. Ioannidis, provided us needed information to guiding decision makers actions to better impact effective results.

He also indicated prolonged effects on social distancing and isolation, to those impacted by the v***s. If without accurate data, decisions of isolation or lock down for unknown period of time, could have similar adverse effects on various aspects of our lives.

Economic crisis, major consequences to the economy, society, and mental health. Unpredictable events could happen including financial crisis, unrest, civil strife, war, and a meltdown of the social fabric.

These are very good warning. Psychology could prove that. This is a warning, that president Trump need to look at carefully.

He pointed out that reliable data is most important in arriving at correct and effective decisions.

Whereas professor Emily Landon, rely on this present condition.

PeterS, you did not even provide any of the informed decision of Dr. Landon her best approach, but relying only on the present condition.

Your objective here PeterS is not constructive, but to spew and destroy. You failed to justify out why Dr. Landon's advice was priority.

But you PeterS, you've chosen to espose hatred of Blade Runner who’ve presented one of the options and analytical decision of Dr. Ionnidis. His objective was positive giving information for decision makers to take, while yours is continued hatred and vindictive vitriol to him, who presented other means to help the government or decision makers.

Here is my opinion. Dr. Ionidis analysis was very useful. While Dr. Landon without further input, I assume she relied on the present condition of shelter in place, that we have.

The decision makers are given these options, and take the best which is effective and needed at the moment. Priorities are used to effectively make the right and effective decision at this critical time.

Mar 21, 2020 06:42:04 #

Radiance3 wrote:

==================== br i We are trying to analy... (show quote)

You think it's wrong to make decisions based on current data?

Mar 21, 2020 06:53:53 #

Canuckus Deploracus wrote:

You think it's wrong to make decisions based on current data?

===============

I did not say, it is wrong to make decision at this current data.

We don't have accurate data at present. My proposal is taking the most effective measure until we are able to analyze further evidence to use to arrive at effective results.

We are in a crisis. Spewing hatred and vitriol to anybody they don't agree with is not human and civilized. That was what PeterS did to Blade Runner.

At this crisis, we don't have time for hatred. We must work together, pray together, to finding better solutions for this crisis.

Mar 21, 2020 07:13:32 #

Radiance3 wrote:

=============== br I did not say, it is wrong to m... (show quote)

All good points

God bless

Mar 21, 2020 07:17:54 #

Iamdjchrys

Loc: Decatur, Texas

Tug484 wrote:

I heard a Dr. say they've had great results with chloroquine and by the 6th day, they're feeling very well.

Chloroquine and another medicine concurrently, tug, but it's only been used on a few patients. Obviously, this needs looking into.

Mar 21, 2020 07:23:08 #

Blade_Runner wrote:

Now, let's see how a professional epidemiologist w... (show quote)

Thats a much better and more realistic article.

Mar 21, 2020 07:33:40 #

Canuckus Deploracus wrote:

Good article... Good advice...

I'm almost finished my second month of "shelter in place"...

I'm almost finished my second month of "shelter in place"...

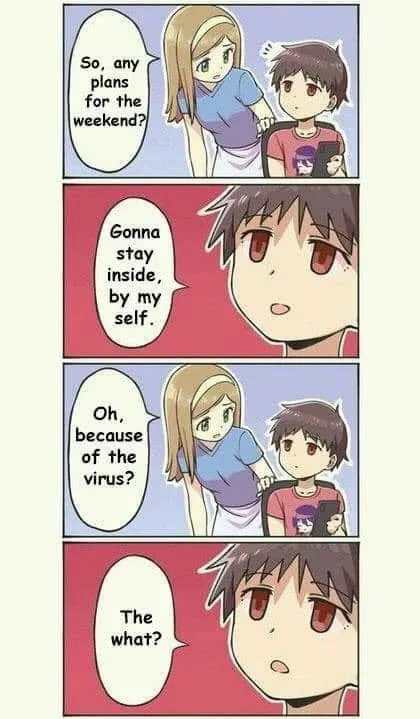

I am certainly on board with this. How often can I be a worthless loafer and claim it's my patriotic duty? I am finding myself more comfortable in the role.

Mar 21, 2020 07:35:38 #

Smedley_buzk**l wrote:

I am certainly on board with this. How often can I be a worthless loafer and claim it's my patriotic duty? I am finding myself more comfortable in the role.

Mar 21, 2020 07:52:28 #

whitnebrat wrote:

Washington Post br By br Kim Bellware br March 2... (show quote)

==============

Of course everybody wants to taking the "Shelter in Place," and hoping the government will handout ration to feed us, until it is bankrupt. I don't see it as the best approach.

As far as PeterS approach is concerned, I think he acts like another v***s, infecting people who differ from his political culture.

Mar 21, 2020 09:31:28 #

whitnebrat

Loc: In the wilds of Oregon

Blade_Runner wrote:

Now, let's see how a professional epidemiologist w... (show quote)

Ah, dueling experts. A classic way to confuse the issue.

At its core, what we're dealing with here is the cost of a human life in dollars.

If we keep everyone home, it costs us all in terms of loss of the economy, jobs, and some businesses.

If we stay open without restrictions, it costs us in terms of the mortality rate and t***smission to other people.

It is, in reality, a classic Hobson's choice. Which one can we afford least?

We report, you decide.

If you want to reply, then register here. Registration is free and your account is created instantly, so you can post right away.