Lip Service

Jan 26, 2020 00:01:20 #

Coos Bay Tom

Loc: coos bay oregon

nwtk2007 wrote:

Politics.

Yeah I know --Raw sewage has a better smell by far.

Jan 26, 2020 06:36:20 #

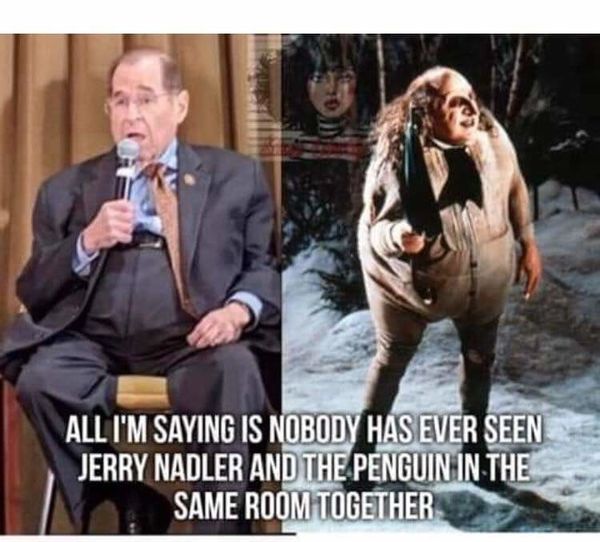

slatten49 wrote: Once again, the King of Memes strikes

Once again, the King of Memes strikes

Once again, the King of Memes strikes

Once again, the King of Memes strikes

Actually there may be some t***h to that meme....

Jan 26, 2020 15:43:37 #

slatten49 wrote:

There is little doubt that the whole t***h is skewered by both sides. That being said, others can now listen to the "liars" from the other side. Figure on the t***h being somewhere in the middle.

In the end...just as in the House...partisanship will most likely rule.

In the end...just as in the House...partisanship will most likely rule.

it will all be over Monday

it's the Republicans perogative

Jan 26, 2020 15:52:51 #

slatten49 wrote:

As Congress moves toward a possible formal impeach... (show quote)

The President invoked executive privilege to deny witnesses and documents. This has been done by past Presidents (including Clinton and Obama), if Congress disagrees with the invocation of executive privilege there is a procedure for deciding who is right. Upon the invocation of executive privilege, Congress can turn to the court to have the subpoenas enforced. If Congress doesn't use the remedy of the court to enforce the subpoenas, it must be presumed that they know the subpoenas are not enforceable. If Congress had gone to court and the court decided in their favor but the President still failed to respond, they would have a case for obstruction of Congress. Without Congress doing this, they have no basis for obstruction of Congress.

As far as the aid is concerned, there was no delay. Delay implies that something was not done by a specific time. The aid was required to be sent by 30 September 2019. The President released the aid 11 September 2019, ahead of the deadline, therefore there was no delay. It would be like a person getting a bill on the first of the month that is due on the 30th. Although it can be paid on the first, it would not be delayed (late) as long as it is paid before the 30th.

Jan 26, 2020 17:10:45 #

slatten49 wrote:

The state of partisanship being as it is within bo... (show quote)

I'm glad you put that emoticon in. I haven't felt that either party represented me since 1970, if I had been paying attention sooner I probably would have noticed. For example Eisenhower was great, but he had many eyes on him. I don't know how many heeded his warning. By the time Johnston or even Kennedy were in office the country had gone to s**t.

Jan 26, 2020 17:12:11 #

Weewillynobeerspilly wrote:

Sure glad im not like that

Term limits.

Term limits.

Yep we certainly need term limits.

Jan 26, 2020 17:16:01 #

Coos Bay Tom wrote:

is it true that trump has threatened senate republicans that their heads would be on a pike if they did not side with him? I am going to look it up and come back here.

May as well look in MAD Magazine. Threatening bodily harm? Think of how that would play to Roberts.

Jan 26, 2020 17:19:08 #

Weewillynobeerspilly wrote:

Sure glad im not like that

Term limits.

Term limits.

Term limits and no lobbyist position after leaving office..Hell, no lobbyist at all, period....

Jan 26, 2020 17:23:31 #

Coos Bay Tom wrote:

You know better than that

Alien, but illegal? The best I can say is he was the Manchurian Candidate.

Jan 28, 2020 21:26:59 #

slatten49 wrote:

As Congress moves toward a possible formal impeach... (show quote)

Blah, blah, blah. Read more extensively and deeply and you will find a common theme among all the agreements and disagreements was that the actions that would cause the impeachment of a president were all actions akin to treason, very serious actions that had or would have extreme negative effects on the country. Nothing alleged in this process comes anywhere close to that.

If you want to reply, then register here. Registration is free and your account is created instantly, so you can post right away.